Platy limestone – geologic definition and its use as a mineral commodity

Jernej Jež, Uroš Barudžija, Sara Biolchi, Stefano Devoto, Goran Glamuzina, Tvrtko Korbar

Possible exploitation of platy limestone in the relatively small project area in Italy was identified on the basis of historical PL usage and outcrops of all PL types previously defined on 1:50,000 scale maps. As PL outcrops are limited and often hidden by soil and human activities, particular attention was given to quarries where outcrops were evident.

Historical exploitation of platy limestone was mainly limited to small local outcrops named “jave” located closer to the villages. Limestone slabs were obtained by means of picks, levers or more rarely chisels. PL was used for different architectural elements (Fig. 2.17).

Extensive field activities have been carried in order to characterize the main properties of outcrops and classify the geomorphological features of both the active and abandoned quarries (such as their position in the landform and their state of activity). Moreover, the exploitation areas have been overlapped with safeguard areas using GIS applications in order to exclude the possibility of conflict with legislation issues. In Italy, the main legislation which deals with the natural heritage and the possibility of quarrying are Nature 2000, the Landscape Obligation, the Hydrogeological Obligation, the occurrence of Nature Reserves and of Geo-sites.

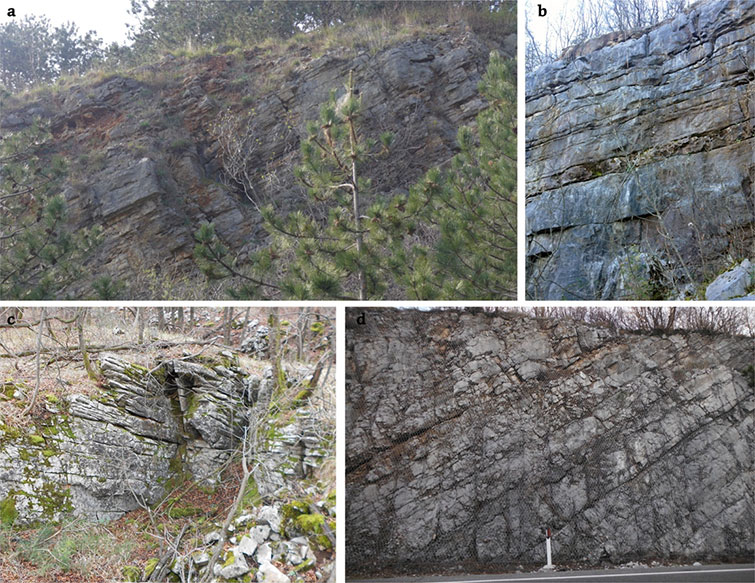

In the Italian part of the project study area, platy limestone has been observed only as limited lenses and horizons within other thick-bedded limestone (Fig. 2.18). It occurs in almost the whole stratigraphic sequence of the carbonate platform (Mote Coste, Zolla, Aurisina Formations) and are both Cretaceous and Paleogene in age. The main observed texture is mudstone, often laminated.

Quarries in total platy limestone successions are absent. Few quarries with limited horizons of platy limestone have been recorded. Where platy limestone crops out, its spatial extent and thickness is insufficient for extensive exploitation. Although the primary activity is massive limestone extraction, they can provide limited quantities of platy limestone materials. They are mainly located in the northern part of the study area, in particular in the Gorizia Kras/Carso and the surroundings of Aurisina (Fig. 2.19). In addition, it was evidenced that also a special type of limestone slabs, the so-called Fractured limestone, were excavated as building material. In this case, the superficial weathering, together with faulting and fracturing on the massive limestone beds, enabled the excavation of some plates of sufficient size for roofing.

The mechanical characteristics of platy limestone change from layer to layer as well as at a level of an individual layer due to various lithotypes, lamination and very heterogeneous successions. Therefore it is difficult to evaluate the mechanical characteristics in general for the entire PL sequence.

A Schmidt hammer was used to define the in-situ properties of the platy limestone material. The lower intact rock strength (IRS) values for the platy limestone compared to the massive limestone IRS indicate the lower resistance of the material. Fractured limestone slabs usually have better characteristics but it is difficult to excavate regular slabs of appropriate dimensions for roofing because of the intense fracture systems.

However, in the Italian part of the project area, the major part of the quarries with limited platy limestone horizons are now inactive and under protection (hydrogeological and landscape obligation and Nature 2000). Consequently, exploitation is strongly hampered. In a restricted number of massive limestone active quarries, the platy limestone quantity is insufficient to guarantee future exploitation.

Platy limestone occurrences are also important from a natural heritage aspect. In the Komen limestone from the lower part of the Aurisina Fm. at Polazzo (Fogliano-Redipuglia) locality, some fish, turtle and plant fossils have been described. Tomaj limestone from the upper part of the Aurisina Fm. displays another layer with very common chert nodules, fossil plants, fish, vertebrates and ammonoids described by Jurkovšek & Kolar-Jurkovšek (1995, 2007). This has been observed in Italy at Trebiciano, Santa Croce, Aurisina and at the Villaggio del Pescatore. The latter is an important “geo-site” (Fig 2.20).